Image Caption: The Port of Urla (wikimedia)

I’ve never been to Urla, a rural district just outside of Izmir that comprises the stretch of coastline extending from Izmir proper out to the resort town of Çeşme, but I imagine it’s a rather nice place. The Urla of my imagination is rather idyllic, sloping farmlands where, amongst other crops, grapevines twirl their way out from a dusty country road, small towns and local shops periodically pop up, off in the distance there’s a textile factory, a bit further there’s a local garrison, and in all, it’s a place where time passes slowly. Most of the time, my research is squarely focused on the happenings in the bustling metropolises like Istanbul and Ankara but lately it’s been taking me to Urla.

What’s brought me there is the compelling story of the Liberal Republican Party (Serbest Cumhuriyet Fırkası, SCF). I will probably write much more about this episode in early republican history later, but the short version is this: Following the 1929 crash and increasing economic pressure and dissension within the ruling Republican People’s Party (CHP), Mustafa Kemal decided to try and let off steam by allowing some of the adherents to economic liberalism in the government to form a new party to compete in upcoming municipal elections. The party, formed in August 1930 by former Prime Minister and then-Ambassador to France, Ali Fethi Okyar, would not be allowed to contradict the core tenets of the Kemalist revolution, but would be allowed to present dissenting views on economic policy in favor of greater privatization, opening up of trade, and other fronts. However, the party attracted a wide swath of support from all sorts of people who were upset with the ruling party — including socialists and pious conservatives. Support for the SCF was vocalized through the press, political rallies, and was occasionally violent. The SCF built a party organization largely on top of the existing Turk Ocakları (Turkish Hearths), and won a great deal of support from the rural bourgeoisie of western Anatolia. They competed, but not particularly strongly, in municipal races throughout the country in September and October, but rising support from pious reactionaries, and an intense set of disagreements with CHP leader İsmet İnönü led Mustafa Kemal to close the party down in November, just four months after it was founded. It’s a fascinating story, and one I’m wrestling with in the larger work of my dissertation. For now, however, let’s get to Urla.

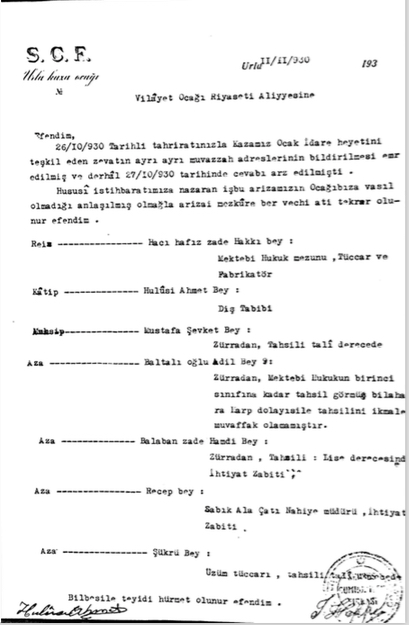

Urla was one of the districts the SCF was able to win in the municipal elections, and in many ways it was typical of the SCF’s constituency — a rural area on the Aegean with more conservative social leanings, run by a few large landholders who ran farms and a few manufacturing outfits. In my research I’ve come across the internal files of the local SCF organization – they were also called “Hearths”- in Urla, including the document below, which lists the Urla Hearth’s membership and administrative council.

The roster, which was sent from the Urla Hearth to the Regional Hearth Presidium in Izmir on November 11, 1930, lists the President, Secretary, Treasurer and four regular members, along with their level of education and their occupations. The President of the party branch, Hacı Hafız zade Ibrahim Hakkı (actually, the second president, he took over from local merchant Mustafa Nuri sometime in early October) is clearly the most credentialed of the party members – a graduate of the law faculty, a trader and manufacturer. There’s a clear professional elitism – or meritocracy – at work in the organization, professionals with close ties to the town center like Hakkı and the secretary Hulusi Ahmet (a dentist) were elected to more prominent positions than the less educated members like Baltalı oğlu Adil Bey, who made it one year through law school before leaving to join the Independence War effort, and now working as a farmer.

Military connections, largely as reserve officers, seem to also have been a sought after credential for party membership. It’s unclear if there were any military barracks directly located in Urla province but it would have served the SCF’s interest in proving its loyalty to the regime, which was the concern that ultimately brought the party down. It also goes to show that the dissatisfaction with the Kemalist-led government amongst the elite veterans of the Independence war was indeed shared by at least a few lower ranking officers and conscripts. But besides that, these documents show that there were indeed social ties in Urla between officers, farmers, and businessmen.

What is clear from reading through rafts of other files on this short lived opposition party is that they were quickly able to tap into social and business networks across the country and establish a fairly well functioning party operation in the span of a month or two. This is astounding particularly for a region like Urla which was decimated a decade earlier in the wake of the Greek invasion of Izmir and the subsequent retaking of the city by the Atatürk-led Turkish forces. Even in a time of economic depression, in a region whose population had experienced a steep decline, these kinds of networks persisted and were activated with relative ease when the right political organization came along. It is a helpful reminder that these rural spaces are never as empty as the can seem some times.

The full story of the Urla Hearth is something I’m going to continue working on, and perhaps some more glimpses will come through in future posts.

One comment